We are back with a post-event reflection on Comunità Grano Alto’s1 recent bread and grain festival, FORNI & FORNAI·E. It was quite a whirlwind event, and, as one of the organizers,2 I was blown away by the different groups who wanted to participate. Given all the engagement, we wanted to fill our Interested Eaters in and talk about the most popular festival event - the bread tastings.

You may have read our previous posts about the Comunità Grano Alto. If not, or if you want a refresher, check out our interviews with members from the Comunità or our introductory article.

A New Kind of Tasting Experience

Most of us are familiar with wine, coffee, and chocolate tastings, but have you ever heard of a bread tasting?

We certainly had not, but we were intrigued. So, during this festival, we decided it was time for bread to take the limelight and for us to explore the wide range of flavor possibilities, from grain to loaf. Our research on bread tasting revealed a wealth of information on a few specialty items, but generally the resources we found were very niche and bare bones.

The Inspiration Behind the Journey

My adventure into the world of grain flavor is set against the backdrop of meeting “Flour Ambassador” Amy Halloran and reading her book “The New Bread Basket.” In her introduction, she recounts:

“I bought good ingredients, but I didn’t think much about flour until I was in my forties when I tasted a certain cookie made with oats and wheat that had been grown, rolled, and milled near where I live in New York State… I could really taste the grains. Their flavor and freshness introduced me to the regional grain revival that was happening right under my nose…”.

Sure, she is talking about a cookie here, but it is the same idea. Often, we think of bread merely as a vessel — a nearly tasteless, crunchy, or soft bite used to soak up sauces (or "fare la scarpetta" if you're with me in Italy), surround a flavorful burger, or hold a hearty sandwich together. Rarely do we savor bread on its own and appreciate its complexity and beauty. The same is true for pasta and other grain-based foods, which I also advocate tasting to appreciate their distinctive flavors fully.

Building a Bread Festival

Bread can have so much flavor at a base level, especially when careful about where you buy it - avoid nameless, faceless white bread brands or sad, cardboard-like whole grain bread. To explore these flavors, we dedicated a few hours of the festival to our version of a “bread tasting”.

Our goal for this event was two-fold: To acknowledge and appreciate the depth of bread's flavor, and to highlight the work along the “short supply chain” that achieves this delectable outcome. To set this up, we united the city and country by bringing together 'couples' or ‘trios’ of individuals along the value chain: bakers alongside their farmers and/or millers, with whom they needed to work closely.

The concept was to reveal the nine months from seed to loaf, akin to the gestation period of a baby. From the farmer planting the seed to the miller carefully milling the kernel to the baker mixing, kneading, and baking the dough.

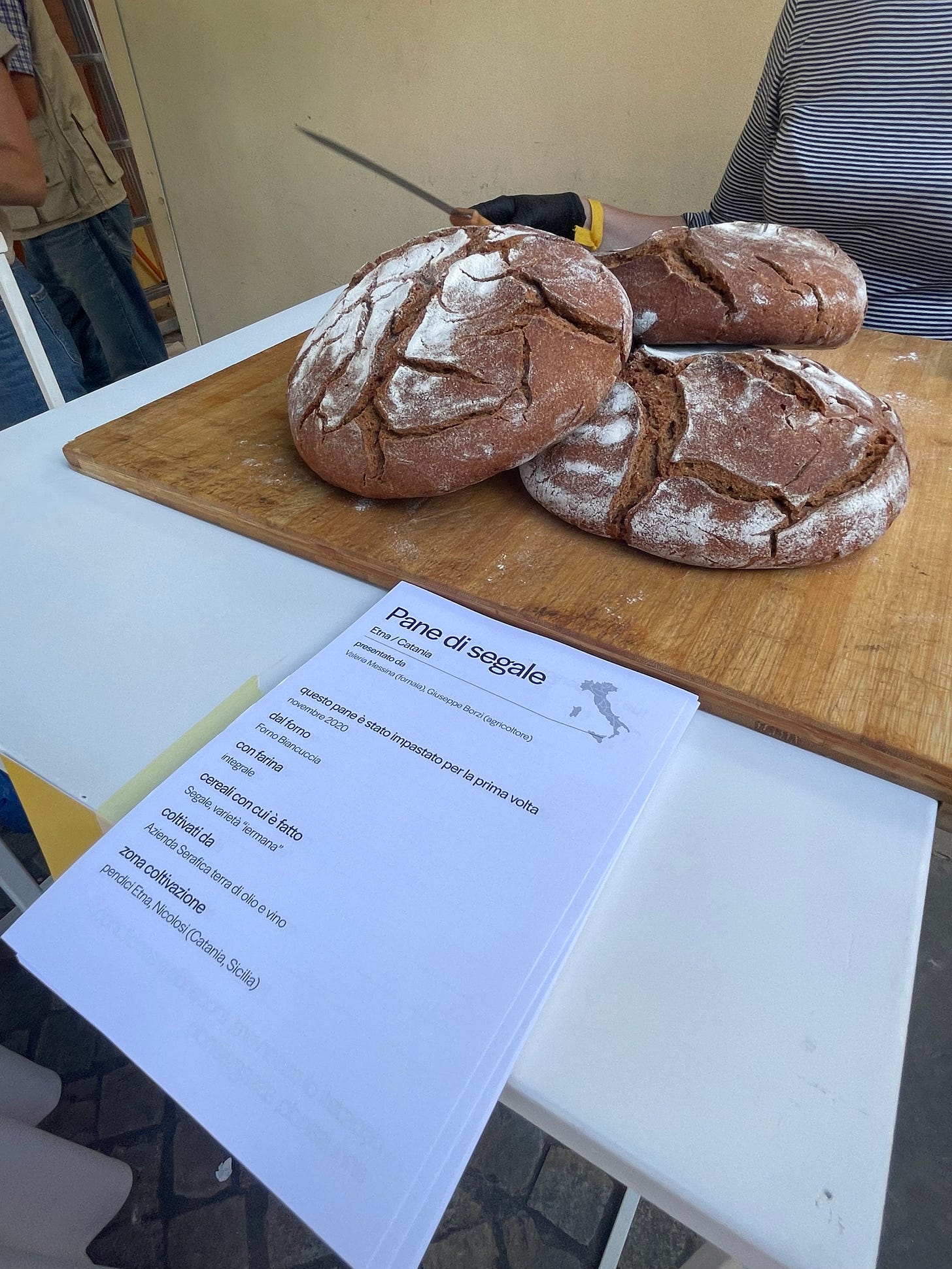

We had a few guidelines. These loaves could have only flour, water, salt, starter or yeast — basta! The tasting focused purely on the flavor of the grain(s) rather than that of the condiment(s). The tasting had four categories, with our guests visiting one or two stations in each category. These were based on the varieties that our groups submitted: rye, grano tenero (soft wheat), single varietal, and evolutionary populations.3

The Depths of Flavor

Of the breads I sampled, I tasted mint, chocolate, fennel, and hazelnut — none of which were added to the loaves! So, where does this depth of flavor come from? Biodiversity, mostly. Yes, other factors, like milling4, fermentation, and baking, play a role in the depths of flavor, too (but that's for another article!)

Unfortunately, most of us have tasted only a limited portion of what is available on this planet — in Eating to Extinction, Dan Saladino reminds us that there are more than 11,000 species within the plant family of grasses, Poaceae. Wheat is often grown as a monoculture (like many other crops) in pursuit of efficiency and standardization. However, this path has led to nutrient-depleted soil and wheat, requiring more fertilizers and pesticides, making our crops more susceptible to disease and less resilient to drought and climate change. Read more here or here.

Beyond taste, using a wider range of grains to support biodiversity is crucial for our planet. By continually planting the same grains on the same plots of land, we strip the soil of its nutrients. This bread-tasting event was an opportunity to showcase the depth of flavor a wide range of grains can offer. The more we realize the range and value of diverse grains, the more we support biodiversity.

What’s the future of bread?

The first loaf of bread was made around 10,000 BC (about 12,000 years ago), so how did something with so much knowledge, history, and tradition become... a bit of a mess? What is the way forward? There are many options: Should we look back and follow tradition, or modernize and follow technology? In my opinion, we must find a balance between the two. Innovation means looking at what we already have and figuring out how to improve it, rather than completely discarding the past.

Perhaps the answer is to just let it be. Let the soil grow what it wants to grow, let the loaf ferment as it will, and support both along the way. We should stop aiming solely for abundance, efficiency, and standardization, and instead appreciate the beauty and depth of what already exists.

In the end, what we need is a good slice of bread that nourishes us and brings joy. There is so much potential, so much possibility. It is a gift to eat a good loaf. After a weekend of gathering around bread, I realize the power of coming together over something as simple as bread. The principle of "less is more" should influence how we approach everything in life.

So, I am curious: when you eat your next slice, what do you taste? Share your thoughts and reflections in the comments. I’ll leave you with this beautiful quote from environmental activist and food sovereignty advocate Vandana Shiva, who we were fortunate enough to have open FORNI & FORNAI·E:

“Throughout history, bread has been a symbol of nourishment of freedom, of solidarity. We talk about breaking bread together. And of course, bread begins in the wheat fields. It begins with the seed. When seed is manipulated for glyphosate, for fertilizers, for chemicals, what you get is a bread that becomes the basis of sickness and disease.

Look at the number of people who are suffering gluten allergies. It isn't the fault of the bread. It isn't the wheat. It's how it was changed for chemicals and poisons. That's why we must have a poison-free food and farming system. And that's why we must recognize that the soil, the plants, health and gut are connected.

The farmer who grows the food, those who process it like the bakers, and those who eat it are connected. We can either be connected through health and freedom or we can be connected through slavery.

It is our choice. You are making that choice. You can be the leaders.”

Comunità Grano Alto is a network of breeders, farmers, millers, bakers, agronomists, geneticists, researchers, advocates, and enthusiasts in Emilia Romagna, Italy, aiming to (re)build relationships along the regional grain supply chain. For more information, check out our introduction article or their website.

Christina 👋 here!

Initially developed by agronomists, evolutionary populations consist of hundreds or thousands of wheat varieties mixed together. They cross freely and naturally; the principle involves selecting seeds with the best traits, such as resistance to weeds and pests, yield, drought tolerance, and allowing them to evolve in their environment. This method supports organic farming, reduces costs, preserves biodiversity, and adapts well to climate change.

Often, you might find yourself consuming this super white, refined flour that contains only the endosperm. The germ and bran, which hold most of the flavor and nutrients, have been removed. Our grains have been stripped of their natural richness and transformed into a blank canvas upon which we map external flavors rather than discovering the flavors within. However, this process calls for a longer article, so we will explore this further in a future Food People article.